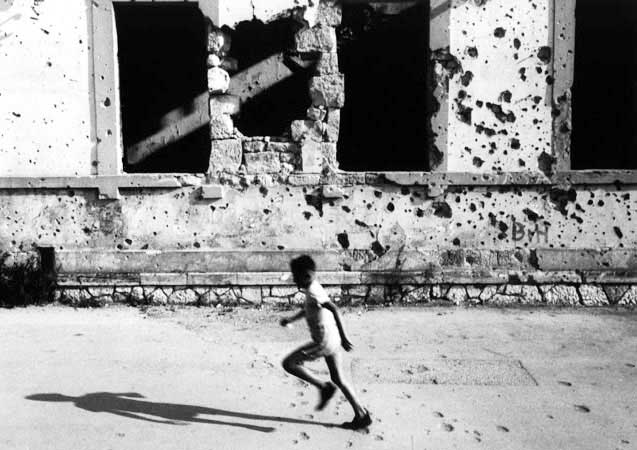

Avlija

They were just two kids playing in their backyard. The avlija, a garden enclosed by a high stone wall, was the only source of normal play for them. Kids like kids, mom and dad let them into the well kept garden to play during a lull in the shelling. A 120mm mortar round came, with random precision, smashing into and through their world only minutes later. Selma, 9, lost her right arm. Mirza, 6, lost the heel of his foot. Both were peppered with shrapnel wounds. Sally Becker would later evacuate them and their mother to Split. From there they were medivac-ed to San Francisco.

Their father, a humble gentlemen named Mirsad, was left behind. He was a man of fighting age. Every army always needs every body they can get, no pun intended. He too was slightly wounded in the leg. My memory fails me as to how and when. I do remember his limp and an improvised bandage around his mid shin area.

As any sane individual would, Mirsad wanted desperately to leave and be with his family. I don't know what or how much information he had about his gravely wounded children, but not being with his kids when their lives were in danger was doing his head in. I was working on a mobile hospital project for East Mostar, a donation from South Africa for the besieged side of the city. Timelines are shady for me. I think we made our escape in November 1993, just after 120 tank rounds had taken out the Old Bridge in Mostar. It stood for over 400 years. It was the symbol of the nation. It was their Statue of Liberty or Eiffel Tower. It was reduced to rubble at the bottom of the Neretva River.

Many years later I was made aware that I was accused of smuggling people out of Bosnia. In all honesty, I never really saw it like that. It seemed so less Harriet Tubman-ish than that. I knew Mirsad from the other evacuations I had done with Sally of wounded children and members of the Jewish community. He was always there, trying to figure out how to reunite with his family. Trying to see if we could take him out. On a very practical level, it seemed impossible, even in the midst of the chaos and lawlessness of war. One side didn't want him to leave because they wanted his ability to tote a gun. The other side was his 'enemy.' Stuck between a rock and a hard place barely suffices in describing this man's dilemma.

Again, I can't remember everything but I do recall with each visit that he became more desperate. His family had been relocated to California. Selma had already begun to undergo the first of her thirteen major surgeries. He wanted out. I had no clue on how to help him without getting both of us shot or imprisoned.

The American Embassy in Zagreb was well aware of Mirsad's plight, however. I was a bit in the dark about any of that. I had met an official from the US Embassy in Zagreb when one of my friends and colleagues was killed on the frontlines in Mostar. Collette's parents couldn't afford to fly her body home to Michigan, so we had her cremated in Split. Me and a few friends brought the urn with her ashes to her funeral in the states. I think the embassy officials name was Richard. He had arranged the cremation and death certificate for her in Split. Those days are exceptionally cloudy. She was our first close colleague and friend to go down. It was September '93 I believe. Whether we admitted it or not, we were all in a bit of shock.

Richard. So he contacted me. I can't recall how or when. He presented me with an official document from the US Embassy with both a seal of approval from the embassy itself and from the relevant ministry from Croatia proper granting Mirsad permission to come to US Embassy in Zagreb. Being that the US Embassy in Sarajevo was not fully functional (or perhaps not functional at all at that point, ne znam), Zagreb was the main US Embassy in the region. They had little or no access to Bosnia and Herzegovina. My guess is that it was too risky and dangerous anyway. So they asked me. I was naively enthusiastic about the opportunity.

I have zero recollection on how we organized it logistically. I know I was in my trademark blue Land Rover Defender. It was a right hand drive. I always thought it would give me better odds under sniper fire. I don't know if Mirsad had the proper papers from the Bosnian side to leave. I'm not sure I ever asked. We made it through those checkpoints effortlessly if memory serves me. I felt I knew Herzegovina, particularly western Herzegovina, like the back of my hand. So there was no fear. Probably just nervous excitement. The adrenaline rushes from back then have yet to be matched. Not even close. I had been working there for almost a year and although it was a completely manic situation, even then I felt at home there. So off we went.

What I don't remember but do know is that the first ten kilometers of our trip had at least as many military checkpoints on both sides. Mirsad sat in the back where there were no side windows. He was quiet. He smoked a lot. Out of nervousness he slightly rocked back and forth. I know we took some back roads. Which ones I have no idea. We reached the border just before nightfall. It was the Grude crossing near Imotski if I'm not mistaken. I did try to time the crossing to the schedule of the South American soaps. As crazy as it sounds, we were much more effective in getting convoys across borders during soap opera times. Even the border guards couldn't be peeled away from the drama unraveling in Buenos Aires. And no, I'm not kidding.

As we approached the border I tried to assure Mirsad it would be ok and to just try and stay calm. If I had butterflies though, Mirsad must have been shitting himself. It was a tense and awkward silence when he took our papers and went back to his little box. Mirsad and I didn't speak. The guard returned. He ordered us out of the Land Rover. He opened the back. The only thing that stood between Mirsad and an AK-47 toting 'enemy' soldier was a clueless American and a waxed eagle seal from the US Embassy. He held the letter from the embassy, staring at it for what seemed to be an eternity. He declared it a fake. My heart sunk. He ordered us back. We were told to return from where we came from. I was angry...'you've got to be fucking kidding me?!'...luckily he didn't speak English. My arguments were in vain. He wasn't having any of it. This attempt was a bust. Or was it?

To be continued.